ㆍPrivacy: We respect your privacy. Here you can find an example of a non-disclosure agreement. By submitting this form, you agree to our terms & conditions and privacy policy.

Views: 2 Author: Allen Xiao Publish Time: 2025-11-21 Origin: Site

Your new product is finished. The housing is made from a beautiful, glossy, hard plastic. It feels solid and rigid. It looks like a high-quality item. Then, the first time a customer drops it, it shatters.

The customer is angry. Your brand's reputation is damaged. You have a costly warranty problem on your hands. How did this happen? You chose a "hard" plastic specifically for its strength.

The truth is, you fell into one of the most common traps in material selection. You confused hardness with toughness. This guide is a forensic investigation into why hard plastics break, and how to choose one that will not.

content:

The promise of a hard plastic is a feeling of quality. It resists scratches. It is stiff and does not flex. This rigidity can make a product feel substantial and well-made.

But this promise is broken the moment the product is subjected to a sudden impact. A remote control slipping from your hand. A child's toy thrown against a wall. A piece of luggage being roughly handled at the airport.

If the wrong type of hard plastic was chosen, the result is a catastrophic failure. A crack. A shatter. A broken product. The very hardness that made it feel good, also made it fragile.

To understand why this happens, we must understand the difference between two key properties of plastic: hardness and toughness.

Hardness is a measure of a material's resistance to surface indentation or scratching. A diamond is extremely hard.

Toughness is a measure of a material's ability to absorb energy and deform without breaking. A car tire is extremely tough.

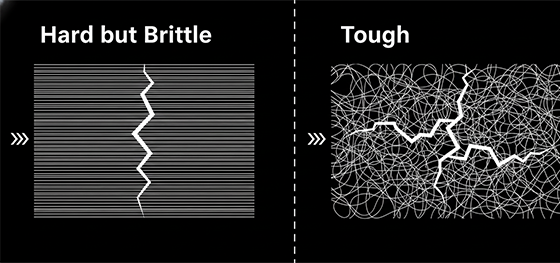

Often, these two properties are in opposition. A very hard material is often very "brittle" (the opposite of tough). Its molecules are locked rigidly in place. When a crack starts, there is nothing to stop it. It travels through the material instantly. This is what happens when glass shatters.

A tough material has a different internal structure. Its molecules can move and stretch. They are entangled. When a crack starts, these entangled chains absorb the energy and stop the crack from spreading. The material might dent or deform, but it does not break.

Some of the most common plastics that fall into the "hard but brittle" category are materials you see every day.

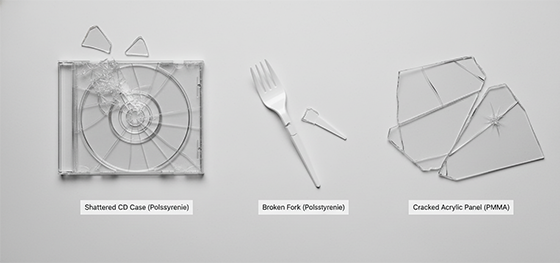

General Purpose Polystyrene (GPPS) is a prime suspect. It is crystal clear and very rigid. It is used to make CD jewel cases and disposable cutlery. And as we all know, they break very easily.

Acrylic (PMMA) is another. It is beautifully clear and very scratch-resistant, which is why it is used as a glass substitute. But it has poor impact strength. A sharp knock can easily crack it.

Choosing these materials for a product that needs to be durable is a fundamental design error.

The goal for most product designers is to find a material that is both hard and tough. These are the heroes of the polymer world.

ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) is a fantastic example. It is hard and rigid, giving products a solid feel. But it also contains butadiene rubber in its chemical structure. This gives it excellent toughness and impact resistance. It is the perfect balance for most consumer electronics.

Polycarbonate (PC) is another hero. It is an extremely tough, transparent plastic. It has incredible impact strength. This is why it is used for motorcycle helmets, safety glasses, and other products where impact protection is a matter of life and death.

Even a rigid plastic sheet material can be tough. A sheet of PET-G, for example, is stiff but also very impact resistant, making it a great choice for machine guards.

Material choice is critical. But good design can also make a huge difference.

Even a tough plastic can be made brittle if the design is bad. The number one cause of failure is stress concentration. A sharp internal corner in a plastic part is a point of weakness. It is a microscopic "crack starter."

A professional manufacturing partner will spot this in your design. During the DFM (Design for Manufacturability) review, an experienced engineer will recommend adding a smooth radius (a fillet) to all internal corners. This simple change spreads the stress out over a larger area. It can dramatically increase the real-world toughness of your part.

This expert feedback is one of the most valuable services you can get. It is the partnership that turns a potentially fragile design into a robust and reliable product. It is about choosing the right material, and then treating it with respect.